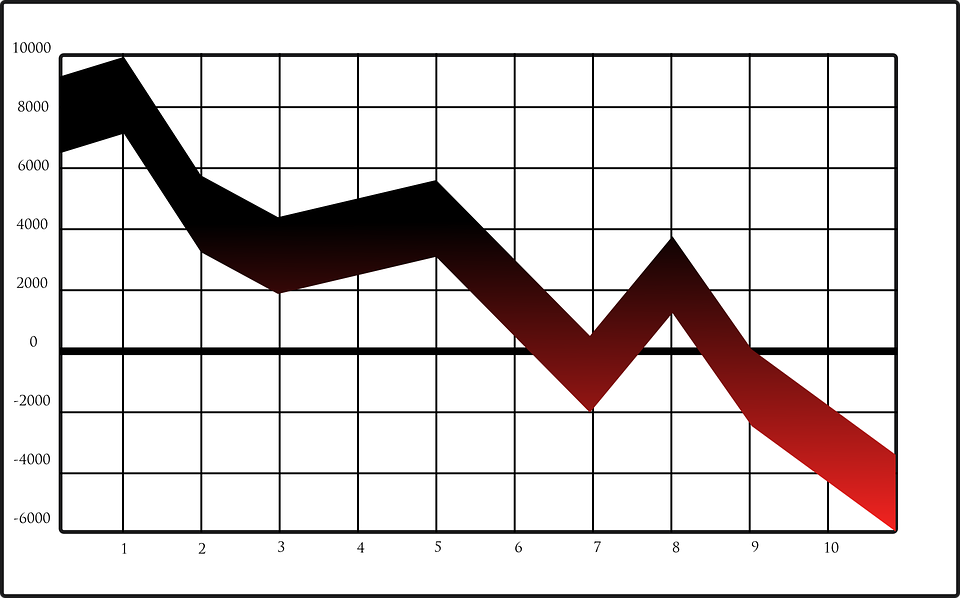

Political risks know no vacation. August 2011 will be remembered as a month of misery, not simply because of the politically induced crash on the stock markets during the first two weeks, but also because of the spreading sensation of angst that the industrialized world might be facing a new economic recession.

Political risks know no vacation. August 2011 will be remembered as a month of misery, not simply because of the politically induced crash on the stock markets during the first two weeks, but also because of the spreading sensation of angst that the industrialized world might be facing a new economic recession.

Put in a wider context, the recent turbulences reflect a trend that has been evolving for some time now, and which entails some worrying implications. The European Union states, the United States, and Japan, have become major sources of political risks due to unreliable and unpredictable political behavior. Political disunity within the EU about how to deal with the debt crisis in Greece and other affected countries of the euro-zone, as well as the escalating dispute over US budget reforms, has seriously contributed to deepening the uncertainty about the economic prospects.

Independent of the criticism that has been directed against the credit rating agencies, it cannot and should not be ignored that the downgrading of the US rating by Standard & Poor’s, was essentially motivated by a political assessment, reflecting the view that “the effectiveness, stability, and predictability of American policymaking and political institutions have weakened at a time of ongoing fiscal and economic challenges”.

Similarly, Moody’s downgraded Japan’s debt rating, referring to continuing political chaos under the government of prime minister Naoto Kan, who eventually stepped down at the end of August. All hopes now rest on the newly elected prime minister Yoshihiko Noda; whether he will manage to take on Japan’s huge public debt, and turn the country into a source of confidence, will be a matter of international relevance.

Regarding the United States, a congressional super committee is expected to overcome the ugly polarization between Democrats and radical Republicans, including those associated with the so-called tea party faction. For sure, this requires striking a deal combining spending cuts and revenue increases, but most of all, starting to collaborate based on the awareness, that ideological battles risk to further poison confidence in the much needed business investments.

The current deliberations within the EU euro-zone may sound more moderate, but they still display fundamental rifts regarding the future strategy for solving the debt crisis and ensuring fiscal stability. The entire debt debacle resulted from a massive political failure to enforce the original Stability Pact which was supposed to underwrite the solidity of the European Monetary Union. The major challenge facing Europe now, consists of enacting reliable and distortion-proof regulation for the new Financial Stabilisation Mechanism, again in order to reestablish trust in a sound governance of the euro-zone countries.

Regarding the controversial debate about the introduction of so-called Eurobonds, it often appears as if this were the remedy which only Germany is blocking out of a lack of European solidarity. It is true that the government of chancellor Angela Merkel is at risk of a split regarding that issue. But essentially, talking about Eurobonds also requires acknowledging the constitutional ramifications of another EU treaty reform. The critical question really is: who is ready for moving from a monetary union to a fiscal union, wherein the member states would have to forfeit their much cherished financial sovereignty and agree to centralizing control over tight budget discipline?

Some might sympathize with further federalizing the EU, or see a fiscal union as a logical and necessary step to sustain the common currency. However, new political risks might be attached to following down that path, particularly those related to the issue of political legitimacy.

The debate about giving up budget sovereignty may alienate larger parts of the national electorates in the member states, including the middle classes, which could lead to a surge of populist and nationalist parties. At the same time, necessary austerity measures deriving from reducing public deficits might produce more outbursts of social protest in a greater number of countries. The risk of increased political instability may, therefore, be too high a price to pay for achieving the goal of fiscal integration in the long run.

Moreover, looking at the economic and financial weight of Germany and the country’s deeply embedded national priority of price stability, it is hard to imagine a fiscal union that would not work based on rules mostly made in Germany. The prospect of real or perceived domination by Germany in that highly sensitive area of state sovereignty would do the project of European integration no good.

As a result, political accountability and reliability needs to be restored at the national level of the highly indebted countries first, signaling a voluntary shift towards fiscal and structural reform, and paving the way to building competitive economies. Only if that consensus is given, further fiscal integration might actually gain political acceptance and increase economic confidence.